Leo Smith – notes (8 pieces) source a new world music: creative music (1973 / 2015)

Nearly eight years ago I shed joyful tears I never expected would fall. America elected its first Black president. For a moment I believed that the inherent racism which defines our country was slipping away. Those tears are now acid rain. Time has told other truths.

The last decade has brought the question of race from the shadows, highlighted the polarization of our country, and left me drowning in disgust. The presented options – apathy, complicity, or outright bigotry. Hope and promise slip away. Blood flows in the streets – more Black and Brown lives, with all their potential, lost to White hands. Corpses and shackled hands illuminate our lily-white tower – a living organ, pumping centuries of racist policy and action.

Regular readers of this site will know that the question of equity – be it ethnic, cultural, gender, sexual orientation, or any other form in which it might find itself threatened, is a major concern of my writing. I believe that our society has been engineered to promote the separation of peoples, and that our creative legacies are a weapon against this. Art, among other things, promotes empathy and shatters the divisions enforced upon us.

Leo Smith’s notes (8 pieces) source a new world music: creative music, first published five years before my birth, and now reissued by Corbett and Dempsey, describes the political and social potential I believe music to possess. I wish that age rendered it irrelevant – that in the decades since its publication we had progressed toward being a more just society, that the question of race, which is at the heart of its conceit, was no longer a concern. Sadly, many of us will find its subtext more relevant today than when it was written.

For most contemporary readers, this book will be a curious artifact. In a world defined by the widespread denial of historical and contemporary contexts, they might wonder how a poetic and political rhapsody in defense of a people’s music (Free-Jazz) could hold value today. To approach notes (8 pieces) within a singular paradigm, for its words alone, muffles its potential. It is a nesting doll within nesting dolls.

Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith is a giant. A profound creative force, and a beating heart of American music. I’ve spent twenty years with his work. Every listen plums unimaginable depths, taking me closer to its core. Smith’s music is the essence of generosity. My respect for the man cannot be summed.

To access notes (8 pieces), you must understand the context from which it grew. For it to operate today, and reach its enduring potential, consider what has changed (and more significantly what hasn’t) in the years since its publication. The book found form during a period of heightened political consciousness. During the late 1960’s and early 70’s, many Black Americans were forced to accept the scope to which White America, and its architecture of power, resented, and were unwilling to address, the demands tabled by the Civil Rights Movement. Laws were passed but rarely enforced. Gross social neglect ravaged. Backs were turned. What began as a fight for equity, evolved into rational pragmatism which addressed the depth, duplicity, and ultimate consequence, of our country’s racist agendas. It birthed revolutionary attitudes toward community and for relating to society. Black America, understanding that there was little opportunity for equity within society’s standard architectures, plotted its exit.

For most, the proposed departure of African America was not geographic. It was a new consciousness of identity, community, and self-determination, enabled by the understanding that Black communities were not accepted and valued by those external to them, and thus not afforded the same rights and support. Rather than fight for a place within a rotten body, many decided to begin again separately, and build a system of support, unity, and pride. This is a core foundation of Black Nationalist and Afrocentric intellectualism – the river that flows beneath notes (8 pieces). The book is a contribution to Black identity and a gesture of solidarity and support.

One of most defined and advanced gestures of collective Afrocentric intellectualism and music is the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). Founded in 1965 on the South-Side of Chicago, Wadada Leo Smith became an early member, and continues as such today. The AACM revolves around a belief in the central importance of advanced African American music, in collective support to realize it, the sharing of knowledge, and the education of the communities in which it sits. Smith wrote notes (8 pieces) as part of the AACM’s working modus, a contribution to its body of work, and its lasting legacy. Though it bears his name, it is a gesture of collectivism, and a gift to his community.

Smith’s writing is a duality. There is explicit content and potential. Though the text only skirts its proposition as such, the book is a social, racial, and political gesture. What it says, versus what is, though bound, are not mutually exclusive. The book is a helping hand. A means for others to understand the possibilities of music, how to approach and continue its cultural legacies on their own terms, while offering tools of technical attack. It’s a users manual for Free-Jazz, focused on the importance and realization of that music, while defending African American cultural legacies, which endure constant attack from outside (White) critical forces. Smith was offering the tools to continue (or perhaps begin). It is a poetic, direct, and beautiful text.

Free-Jazz is not the force in African American culture it once was. It begs a question. If not just a historical document, or fodder for nerds, how does it does this text live on? The answer is simple. Times have changed, but the social and political reality, though masked in other cloth, is much the same. If the years following Obama’s election have offered a lesson, it’s that racism is alive and well in America. It infects every aspect of our lives. Whatever color, no one is free from its clutches.

These have been dark years. We’ve cloaked ourselves in the belief that that our society is just, and that the election of a Black president renders accusations of racism mute, while countless people of color are murdered by White hands with no consequence. Fear of the “other” pins down our borders, suffocating the diverse society we might be. Gentrification attacks and shatters ethnic communities. Wages stagnate. Access to education drops. The prisons overflow. Obama’s attempts to make a more just society have been blocked unilaterally by the Right-Wing, not only for their content, but because they were offered by a Black man. The denial of his voice and legacy. Were he to succeed, the suppressed African-American vote might see its potential, and threaten a balance founded on inequity, and as old as the country itself. We cling to the idea that we are on the side of the angels. Under the veil lies another country. An unjust society, raised on broken backs. We are racist. We are selfish. We are wrong.

Within the horror of these times, the bubbles are rising. Movements for social justice, spearheaded by the African American community, are coming to the surface. Forced into existence by our government’s unwillingness to respond to the grossest spectrum of injustice, they understand their opposition. That the cards are stacked against them, and only through self-determination and autonomy can they respond to systemic institutionalized racism. Much of America is blind, not understanding the contexts of their fellow citizens, or the oppression they endure. They believe poverty is to blame, and that being poor is the fault of those who suffer it. What eludes them, is that the economic plight of Black America, as it has evolved since the late 60’s, is an endurant and calculated system of retribution by conservative policy makers, conceived as punishment for the Civil Rights Movement’s attempt to disrupt the social and economic balances of power. It is suppression, prevention, and the production of profit for the prison industrial complex. The police brutality that destroys and claims so many lives is one arm of this beast. The architectures of power don’t just look away, they profit from the condition.

The nature and meaning of the radical social gestures of the 1960’s and 70’s has largely been lost or suppressed during the decades that followed their unraveling. Our visions of that time are riddled with cliche and failure. Few know that sabotage dealt the deadly hand. It wasn’t a lack of potential. While our lives are laced with the belief that idealism is a fool’s errand, there’s another history lying beneath the surface. One of dreams and near success. Of a different reality. A dangerous history, which shows what is possible, and a manual for the future. There’s a revolution brewing. I don’t know its form, but there’s only so much people can take. It will need guidance, and in one small way notes (8 pieces), with its context, might offer it.

I’ve been looking for a copy of notes (8 pieces) for years, and was thrilled to find that it had been reprinted on a recent trip to Chicago. Corbett and Dempsey is a Chicago based gallery, co-run by the wonderful writer John Corbett, which has been doing incredible work to promote neglected cultural gestures since its founding. I can’t thank them enough for bringing this book back from the shadows. Though the book was written for Black musicians, during a different time, I believe everyone should read it. It gives access to an understanding toward the creation of this remarkable music – a means to understand it from the inside. More importantly, it represents the importance of generous acts of social concern, and is a model for the future – something none of us should disregard. Because I decided to include it in my series Songs Without Music, which explores a text with a group of recordings, I was presented with a challenge. Should I focus on Smith’s discography alone, or on albums made by members of his extended community who embody the spirit he proposed? I decided on the later. Each of these albums was released privately either by the artist or a peer. They are gestures where both production and art are self-actualized acts of creative music. They embrace the revolutionary spirit of the era, and also happen to be some of my favorite records of all time.

Leo Smith – Creative Music – 1 (Six Solo Improvisations) (1972)

Free-Jazz is a profoundly complex music. It’s drawn from the deepest realms of emotion, experience and intellect. Its history is threaded with singular, remarkable, and challenging gestures. Some of the most exciting are captured on recordings of solo improvisations. These gestures, which are most notable among members of the AACM, push an artist to the brink of their skills and expose their towering talents. The solo improvisation offers its creator nothing to respond to beyond the depths of self. It exposes and offers no shelter. It provokes my profound respect. Creative Music – 1 (Six Solo Improvisations) is one such gesture. Privately released on his imprint Kabell – this the first issue under Smith’s name. It seems the album was not well received upon its release, and may have prompted Smith to write notes (8 pieces). The text directly answers criticisms it faced, and offers an analysis of each of its compositions. Prior to its recording, among other projects, he worked with Anthony Braxton, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, and as part of the ensemble that recorded Brigitte Fontaine and Areski’s remarkable collaboration with the Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Comme A La Radio. The ambitious and exposing nature of this album is a testament to Smith’s temperament and talent.

Creative Music defies easy categorization and is remarkably singular. Smith’s sensibility is thrilling and deeply personal. Nothing is held back. It ushers you into the man’s intellect and emotional depths. Smith’s task has always been ambitious. Rather than trying to further the ideas of others, even in his earliest gestures, he attempted to break from tradition and venture into new territory. The distinct character of Smith’s music is striking. The language is his own, but flows from a deep history of African American experience and sonic legacy. Rather than following the progressive thread of his peers, he continuously distills thousands of years of music and culture and begins again. It is profoundly beautiful.

The album is an incredible display of restrained notes which mold themselves into an unmistakable sorrow. Despite the already exposing nature of its form, Smith places himself at further risk by broadening his sonic pallet into sounds beyond his chosen instrument (the trumpet), by lacing it with compositions for percussion and flute. Not only does this make the album more engaging as a whole, but also brings an incredible depth to its range of composing. It works as a single bound gesture in which each piece stands totemically. On most records I own, there are are compositions that separate themselves and rise to the fore. On Creative Music.., there is an incredible sense of balance. The sonic pallet and choice of notes and rhythms fold across time into each other. They are in constant discourse. The rattle of “tiny instruments,” the sputter of the flute, the bleat of the trumpet, though sparse and restrained, become a rattling explosive whole. Unmistakably a towering achievement.

Abdul Wadud – By Myself (1977)

Abdul Wadud is an amazing figure in Free-Jazz, and one of its few cello players. I’m particularly drawn to the bowed strings in Jazz. Not only does their sustain, timber, and attack broaden the sonic landscape, it clarifies relationships with other advanced forms of music. Many listeners have poor ears and bigoted minds. They associate Jazz with “light” entertainment (John Cage’s absurd dismissal of it might illuminate this). For those embracing this position, Wadud takes great strides in shattering it.

A player of profound talent and insight, Wadud began his career as a member of Ohio’s remarkable Black Unity Trio. He spent a number of years studying and playing Western Classical music, before going on to participate in dozens of noteworthy collaborations with members of The Black Artist Group, The AACM, and Frank Lowe. I’ve always felt that he was grossly neglected, both by recordings and history. BY Myself is the only recording that finds him at the helm. As the title suggests, it’s a series of solo improvisations, and like the previous entry by Wadada Leo Smith, is filled with profound vulnerable beauty. Privately released on his own label Bisharra, it’s reasonably rare, but worth the wait.

There are very few albums of solo improvisations that achieve the heights of Wadud’s gesture on By Myself. It’s a record I find my self endlessly surprised and moved by. Each listen makes me wonder if I’ve heard it before. The range of playing, and the ease at which that diversity folds into itself is astounding. A singular statement of individuality, drawing from the broadest cultural legacies of the American diaspora. These hints never rest for long. His playing ranges from sorrowful and melodic, to percussive, and delves into remarkable tonal relationships which threaten your ears with blood. It touches territory expected by listeners of Free-Jazz and avant-garde music – screeching fury, to others which are playful and inviting -flirting with pop melodies you can never place. By Myself is an incredibly honest recording. It doesn’t feel composed. I seems to have flowed forth. There is no artifice. Nothing to prove. Nothing between you and its creator. It’s an amazing journey which I recommend you take.

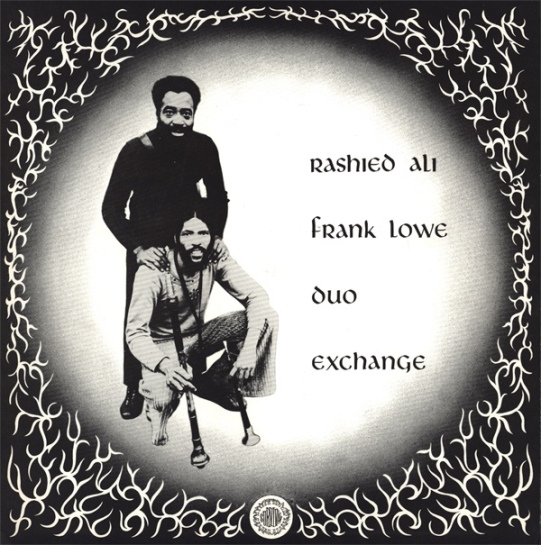

Rashied Ali / Frank Lowe – Duo Exchange (1973)

Duo Exchange is a near perfect document of the incredible fire within advanced forms of Black creative culture during this period. I’m a fan of nearly everything Rashied Ali and Frank Lowe touched, but this album rises to the top. Together they create a force beyond the parts. It’s a fierce blast of pure energy. After it appeared on Thurston Moore’s Top Ten Free Jazz Underground, it became incredibly scarce, and subsequently took me many years to find my copy. It was privately pressed on Rashied Ali’s Survival Records, so I doubt that many copies are out there. Of the two, Rashied Ali’s name is probably more well know, particularity for his work with John and Alice Coltrane, Archie Shepp, and Marion Brown, but also for his remarkable documents as a band leader. Frank Lowe is one of my favorite saxophone players, and though he did belong to Sun Ra, Alice Coltrane and Don Cherry’s ensembles at points, the bulk of his career is marked by more singular gestures as a leader and working relationships with musicians at the outer reaches – Noah Howard, Joseph Jarman, Billy Bang and Joe Mcphee. His tenure in those realms ushered him into the hands of neglect. I’m a fan of nearly everything he touched, but this album and Black Beings released by ESP the same year, rise to the top. They are both filled with a profound energy and charged with creativity. Ali and Lowe bring to focus what was wonderful about this era of Jazz. It was a period of great political energy and creative ferment, but also one where many musicians where faced with hard choices. As audiences drifted toward more accessible musical forms, the question of creative integrity and survival began to rise. Lowe always preferred the more autonomous territories of music, but Ali had different options owing to his work with many of the most renounced names in Jazz. He could have taken a different path. From the early 70’s on, Ali preferred gestures made with a collective spirit. He opened his home as a venue (Ali’s Alley) to support advanced creative pursuits and began his own label. He chose self-determination over interaction with the mainstream. I expect that his collaborations with Lowe grew from this spirit. We’re lucky to have it. Within its sides we find Ali at the height of his powers, his playing is relentless and driving. He takes Lowe, who begins with bluesy restrained lines to the furthest reaches of his emotions and aggression. A storm of energy, and an onslaught which only gives relents briefly for intricate solo gestures by each player. Easily one of my favorite documents from this period.

Arthur Doyle Plus 4 – Alabama Feeling (1978)

Arthur Doyle is something of an enigma. Free-Jazz fans know and love him, but his name is rarely mentioned in the annals of history. There’s very little information about him readily available. He was a notable contributor to the New York “Loft Era” of Free-Jazz, playing in countless live collaborations, but is represented by only a slim number of recordings. In addition to this remarkable outing, he features prominently on two of my other all time favorite Free-Jazz records – Noah Howard’s Black Ark, and Milford Graves’ Babi Music. Alabama Feeling was issued in 1978 on Charles Tyler’s Ak-Ba Records, and is one of the fiercest documents of Free-Jazz. It is a brick to the face. A howling storm of creative energy called forth from all of the anger raging within the African American community at the time. It is the sound of revolution and retribution. It’s an album that forever stays in my listening stack and rarely returns to the shelves. Doyle was a player of remarkable energy and dexterity. His presence and importance during the era is often overlooked. If you want to find out how punk Free-Jazz was, this is the place to start.

Clifford Thornton – Communications Network (1972)

Clifford Thornton is the perfect illustration of the the meeting point between radical politics and advanced music. He began his career playing with Sun Ra’s Arkestra, and though he’s only featured on one Saturn release, I wouldn’t discount the significance of this early association. Ra’s social and political contribution is often neglected. People take him at fave value, reducing many of his efforts to creative eccentricity. Ra’s world was far from what it seemed. Rather than stage-fancy, it was a calculated attempt to reconcile a deeply racist context. Before the civil rights movement, he created the architecture for an Afrocentric alternative. A secondary world – owned by Black Americans. A place of safety and pride. For self-determination and ideals. As the perception of potential changed, Thorton’s terms for relating to a racist context evolved into direct confrontation. It seems likely that Ra’s proposals laid that foundation. During the 60’s and 70’s, Thornton was drawn toward Black Nationalist movements through his friendship with Archie Shepp. He was also thought to have been a minister of culture for the Black Panther Party. France believed him politically dangerous enough to bar his entry, an act which subsequently damaged his career. Despite setbacks, Thorton recorded prolifically with Shepp, and produced a number of recordings as a leader, all of which are remarkable. Communications Network is one of my favorites. It was released on his own Third World Records, and is an incredible display of the diverse range in his abilities. The first side is a rising tide of sound and energy – Free-Jazz with the brakes removed, while the second is more delicate and restrained, laced with poetry by Jayne Cortez (Ornette Coleman’s wife). It’s a lovely album that I can’t recommend enough.

Revolutionary Ensemble – The Psyche (1975)

The Revolutionary Ensemble are one of my Favorite AACM projects. It featured Leroy Jones on violin, Sirone on Bass, and Jerome Cooper on drums and percussion. Sadly, with the passing of Jerome Copper last year, none of its remarkable members remain with us. What I love about The Revolutionary Ensemble is how fluidly they crossed between the multiple creative concepts of their era. They at once embraced sororities usually found only in large ensembles, the fire of Black-Nationalism, and the complex approach to composition born in the AACM. They are one of the most exciting creative collaborations of the period. I love all of their albums, but have chosen The Psyche because it was self released on their own RE: Records – thus an extended gesture of self-actualization and control. The album traverses the divers territory for which the ensemble was known. It delves into the sparse intricacy of each of the players instrument, forces complex relationships and dissonances, and grows into deep grooves. It’s a fantastic ride through the endless possibilities of improvised music.

Pingback: The Abdul Wadud Ensemble, Studio WIS, N.Y.C., 1980 – The Hum Blog