When I originally conceived of writing about the remarkable efforts of Cafe Oto in London (Saint Oto), my plan had been to profile both the venue and its subsequent label Otoroku. As I progressed, it became apparent that each was worthy of a distinct focus. This is effectively the second part of that gesture.

Oto was central to the decade I spent in London. During those long grey days, it coaxed me from the house, offered community, wrapped me in sonic adventure, and reminded me of life’s wonder and joy. I’ve witnessed countless creative gestures, towering to unexpected heights, within its walls. Oto is an act of profound generosity, offering shelter and support to art forms whose ambitions place them in the shadow of neglect. It has no equivalent. In addition to all of its incredible accomplishments, the venue records nearly every show in its sprawling and diverse program. What began as a selfless gesture, founded on a belief in the artists who graced their stage, came to capture some of the most exciting music made anywhere in recent years. It’s an incredible archive carrying creative accomplishment, which under normal circumstances would be lost, to the future. A few years back, my friend John, who was running the program, mentioned the he and Hamish (The venue’s co-founder) were considering founding a label to issue some of their favorite recordings. I applauded the idea. My selfish desire couldn’t be restrained. The possibility of revisiting so many wonderful evenings was overwhelming.

Record labels are a tremendous amount of work. While we easily acknowledged and applaud the efforts of an artist, we rarely consider what happens after the recording process is complete. Hamish and John’s struggle to bring their recordings to a larger audience snapped this sharply into focus. Time passed, set backs were dime a dozen, but eventually Otoroku was born. As the records slowly to crept into existence, they didn’t disappoint. Each is a document of creative forces unleashed within the venue. Some are singular gestures, others are drawn from multiple performances. I was lucky to be in attendance for many of the shows now embedded in wax. I’ve chosen five to profile. They highlight many of the things that make Oto remarkable. Four of the five are cross-cultural collaborations, with the fifth being a solo gesture. Like so much of the venue’s program, we find artists coming together from diverse backgrounds, establishing common ground, and conversing. We hear the fruit of relationships born on Oto’s stage – a forum where artists bridge gaps and build sonic metaphor. They speak without restriction or expectation. Though it is impossible for any recording to capture the energy of the room, these are some of the finest recordings of experimental music and Free-Jazz I can think of. They are a lasting testament to Oto’s incredible work. An ark for generations to come. When John left London for Stockholm last year, his reigns to Otoroku were handed over to my friend Mark Harwood who runs the wonderful Penultimate Press and works under the moniker Astor. It’s in good hands. While we were in London recently, I saw both Mark and Hamish a number of times. They told me of their hopes for the future of the label, and things are looking up. Keep your eyes peeled for a growing catalog of wonderful things. For now their discography is thin, but dense with wonderful sound. These are some of my favorites.

Decoy With Joe McPhee – Spontaneous Combustion (2013)

I hope Joe McPhee’s name is familiar. He’s a giant in the world of Free-Jazz, whose incredible legacy dates back to his work with Clifford Thornton during the late 1960’s. The depth of McPhee’s music is doubled by his remarkable ideas and approach. They sculpt a world of sound which actively defies definition. Unlike many of his peers, whose music largely grows from the legacies and architectures of Jazz as they encountered it, Mcphee’s creative practice stems from a cross-theoretical and disciplinary approach, easily highlighted by his work with the composer Pauline Oliveros, his interest in electronic music, and the ideas of Edward de Bono. Decoy is a trio made up of three of the shinning lights of British Free-Jazz, the piano/ organ player Alexander Hawkins, the bassist John Edwards, and the drummer Steve Noble. Edwards and Noble are two of my favorite musicians on the planet. I’ve seen them play in countless incarnations over the years. They are both remarkably ambitious players who push themselves and their collaborators to unbelievable heights. This album is a honky, scrappy and aggressive outing, which often stands apart from other similar sonic adventures because of Hawkins’ organ playing. As a rule, I’m not a huge fan of the use of an organ in Jazz, but his command of the instrument adds a grinding elasticity to the tapestry. Every realization of improvised music is dependent on successive responses by each musician. One action leads to the next. Mcphee’s contribution to the writhing sonic landscape is fascinating and unexpected. His interventions, which shift from trumpet to saxophone, are decidedly restrained, and held close to his chest. At once intuitive, personal, emotional, and carefully chosen. He’s composing in real time with a depth that few people can access. It’s an incredible dichotomy where Decoy and McPhee push against each other and drive converging tectonics into a mountain. This was Otoroku’s second release and remains one that I return to again and again.

Roscoe Mitchell, Tony Marsh, John Edwards – Improvisations (2013)

Roscoe Mitchell was one of my earliest Free-Jazz heroes. The Art Ensemble of Chicago were instrumental in drawing me into the world of Jazz, and Mitchell’s solo efforts, which predate the AEC and continue today, have remained endlessly rewarding. He was one of the first people I went to see after I moved to Chicago, and I’ve continued to keep up with his efforts every chance I get – including his astounding two night residency at Oto this past October. If I had to pick a favorite living sax player, he’d be it. Watching Roscoe is fascinating. He’s two people. Before, between, and after a set, he sinks into the shadows, humbly trying to take up as little room as possible. It’s easy to forget he’s there. Onstage he’s one of the fiercest consuming presences I’ve ever seen. He fills the room and makes allowances for nothing. You’re smashed against the walls. Roscoe’s playing is nothing short of profound. His skill, technique and individuality is second to none, but that’s no mystery – he was regarded as one of the best sax players of the 60’s and 70’s and he’s never backed down. What makes him special comes from another place – the thing Coltrane and Ayler possessed. Something skill can’t achieve. Call it spirit, emotion, or whatever else. It’s beyond words. Roscoe’s music is mystical and ecstatic. It’s drawn from other worlds, taking you to the outer realms with every breath. Seeing Roscoe live has never ceased to be a revelation, and he gets better with every passing year. I own dozens of his records and even more that feature him. Nothing compares to what he places into a room. This album comes close. Roscoe’s playing with the drummer Tony Marsh and bassist John Edwards is intricate, sophisticated, and heart-wrenching. It nearly brings me to tears every time I let the needle drop. It is as good as Free-Jazz gets. It avoids the predictable with profound restraint. Every second is drawn from the heart and carefully considered. His interplay and response to Edwards and Marsh is intoxicating and completely beyond prediction. They match him at every turn. Few records take you the places they go. If you only have the money for one record, make this it.

Otomo Yoshihide – Piano Solo (2013)

I’ve seen Otomo Yoshihide a handful of times at Cafe Oto, but can’t remember if I was in the audience the night this was recorded. He’s always been one of my favorite Japanese musicians and I was grateful when they first brought him to London. Yoshihide has had a long, varied and adventurous career. Nearly everything he does is worthy of attention. I’m particularly drawn to his restrained minimal work and his focuses on resonance. I spent a lot of time with his album Cathode during the late 90’s and early 2000’s, and still hold it up as one of the best records of the era. Piano Solo is possibly my favorite of his albums. It’s reasonably short. Each side rounds out around twelve minutes. For its brevity it doesn’t disappoint in intensity. You could call it Minimalism, though it bears little resemblance to the standard idiom of that music. Yoshihide builds his sonic pallet from bowed piano strings and their captured resonances. This is not a polite record. It’s a harsh, scrapping and riveting adventure in sound. Rather than embracing the potential intoxicating beauty of bowed strings, Yoshihide takes us to the other end of the spectrum into their abrasive intricacies. It’s intimate, surprising and overwhelming. Resonances wash over you and beat at the bottom of your spine. Despite it’s construction being fairly simple, Yoshihide manages to make these brief sides feel like a sprawling adventure, beckoning you to returned again and again.

Broetzmann, Adasiewicz, Edwards, Noble – Mental Shake (2014)

This record draws from two back to back nights of performances by this quartet. I was in the audience for both evenings and can’t begin to explain how incredible they were. At the end of each evening, I begged John to make them a priority for an upcoming release. There was no question in my mind that these sounds needed to be heard by a larger audience. It took almost a year, but my dream came true. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen Peter Broetzmann at Oto. It’s a big number. I’d been aware of him for a long time before moving to London, was curious, but had never gotten around to giving him much of a chance. As I mentioned in Saint Oto, for many years European Free-Jazz was something I struggled to take seriously. Broetzamann was a major contributor to the destruction of that conception. Having seen Broetzmann, Edwards, and Noble in countless ensembles over the years, it was Adasiewicz’s Vibraphone playing on these nights that offered the greatest revelation. He’s a force to be reckoned with and made me rethink everything I knew about his chosen instrument. These recordings are among the very best of contemporary Free-Jazz. They feature breakneck improvisations filled with fire. Broetzmann lays out all he has, while Noble and Edwards push him on and on. Adasiewicz bridges territory and pushes harmonic relationship to an improbable point of sophistication. Despite European Free-Jazz having grown on me greatly and becoming a deep passion, I still feel that it often lacks next to its American counterpart. Broetzmann is a player of energy, aggression, and intellect – he’s Punk. It’s my impression that the emotional depth of the African-American avant-garde has eluded European realizations of Free-Jazz. It doesn’t lack emotion, but is missing a command over its range, favoring single dimensions, or intellectualizations of their display. Broetzmann’s playing can be an example of this. It’s smart, energetic and exciting, often stretching into revelatory territory, but rarely offers access to his humanity. He risks the playing an idea of music, rather than ushering it forth. This album is different. It displays everything he is capable of. Emotional depth oozes from every seam. Despite my deep respect for all its players, Adasiewicz seems to have made this possible. He is a player of remarkable talent, depth and range. His command over his instrument is mesmerizing, and his ability to bridge between players is astounding. The vibraphone is at once a harmonic instrument and a percussive one. Adasiewicz takes this to new levels. He inflates the rhythm section to three, while pushing Broetzmann’s tones and emotions to new places. It was a stunning thing to behold, and leaves me grateful that I have this album to take me there again and again.

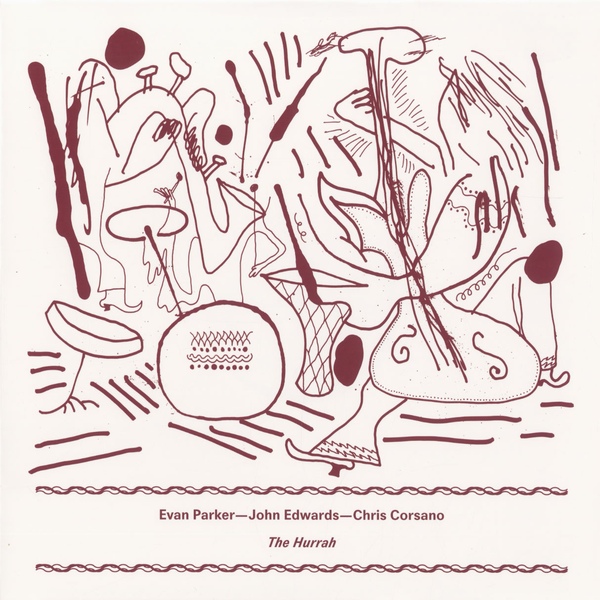

Evan Parker, John Edwards, Chris Corsano – The Hurrah (2015)

Man what a line up! This is one of Otoroku’s more recent releases. Despite their massive achievement of incredible recordings, you become instantly aware why this one rose to the top. You’ll notice that John Edwards features on four of the five of the recordings here. This isn’t an accident – the man is incredible. He’s easily the most exciting bass player I’ve ever seen. Even during lackluster gigs that don’t find their feet, I’m happy to watch Edwards play for hours. He’s a marvel. Chris Corsano is someone I’ve been following since the early 2000’s with ever growing respect. His drumming and sensitivity consistently shatter expectation. Every time I’ve seen him, it’s been thrilling, diverse, and always tuned to his collaborators. There’s no better American drummer of his generation. Evan Parker is a player connected with my historic affection for Derek Bailey (though that story didn’t end well). I’ve seen him dozens of times over the years, always had high expectations, and have rarely come away feeling totally fulfilled. I think he’s best as a solo performer. In ensembles he often feels stilted, unsure of how to respond to another player’s offerings, and reliant on well trod territory. Most of the times I’ve seen him it feels more like a display of Evan Parker, rather than an adventure with him. I have to account for my own tastes. Maybe that’s all it is. There are things I want to hear, or places I want to go, and Parker, who is obviously an incredible player, rarely takes me there. This record is something different. It makes me happy, because it shows him at his best and reminds us why he’s so highly regarded. Parker has a kind of traditionalism to his playing. Normally it bothers me, but here the slow bluesy lines and references to other eras are raw and emotive, providing the perfect foil for Corsano and Edwards rapid fire rhythmic onslaught. As the two slip and slide into each other, Parker groans and grinds between them in perfect conversation. I’ve always been a big fan of Edwards work with the bow, and it really stands out here, almost making the record on its own. It’s a killer album of three players at the height of their powers. Definitely highly recommended.

-Bradford Bailey