The 80’s was a bad time. As optimistic visions of new structures for living, politics and creativity, proposed during the 1960’s and 70’s, sputtered and died in the face of developing social and economic challenges, the post-war generation turned inward. For some it was a matter of survival, for others the cynical temptation of material gain proved too seductive to resist. Some simply crumbled in disillusionment, mourning dashed dreams. Revolution is hard work.

The rapid forming context of the 1980’s brought to realization some of the most vile ideologies the world has known, which though very much with us today, reaped unfathomable damage during that decade. This is the era of Thatcher and Regan – of deregulation, greed, attacks on social protections, and bigoted public policy. This is the time of the Crack and Aids epidemics, which provided the architectures of power convenient mechanisms of social cleansing, and for unraveling of political momentum that grew within African American and Queer communities during the 60’s and 70’s. Members of the Left and advocates for social justice crumbled at the hands of masked genocides and neglect. The Right turned its back as the bodies piled high.

The Right’s ideological position, like a virus, greedily consumes the energy of its host. Death and destruction follow it where ever it goes. It stands in opposition to the moral philosophies of nearly every religion, is counterintuitive to most rational structures of thought, and is ethically suspect on every count, yet its popularity and sway are as old as time. Neither political polarity has ever managed enduring support. As the elections swing one way, it seems inevitable that in time will swing to the other. Our memories are damned to be short. History’s repetition the result of ethical high-mindedness, generalized apathy on the Left, and the Right’s willing disposition to greed, fear mongering and subterfuge. Practices belie policy and rarely bring the world to balance.

All political power understands the importance of the arts. The Left does its best to fund and support them, while the Right (Fascists, Bolsheviks, Khmer Rouge, Republicans, Tories, etc) has historically done its best to undermine and destroy them. The arts are the voice of the people. They speak of our dreams, bind us together, give us hope, and form a vision of our potential. In a true, progressive, and uncorrupted form, they are the purest realization of democracy. In so being, they are a threat to a Right-Wing world view.

I value all of the arts, but consider music to be the most important and democratic. From the street to the concert hall, it brings the broadest spectrum of possibility into the lives of others – at once political, poetic, empathetic, emotive and inspiring, captured in a language that only needs intuition to understand.

Though corporate media dominated the airwaves, pressing plants, and distribution of music during the 60’s and 70’s, they were out of their depth. Youth and countercultures rose and fell too quickly for them to fully understand the qualities of their product, or the demand with which it was met. To survive they were forced into the hands of artists and audiences, and inadvertently let loose profound creative forces that were opposed to their own interests. As the dreams, ideologies, principles and creative ferment of the 70’s began to fade, the early 1980’s gave the industry opportunity to reassert its influence and control. They greedily snapped it up, and for a new apathetic generation, gave birth to music that no longer sprang from the brilliance of artists, but from corporate boardrooms. “Artists” and their music were engineered to create demand, thus nullifying the potential of art, and its danger to (Right-Wing) corporate interests. Anyone determined to make music entirely on their own terms, as pure art, was forced underground and effectively silenced. This context should snap into focus why nearly the entire first iterations of Punk and Post-Punk were housed on major labels, and why the second and beyond were on underground and independent labels.

The legacies and realizations of Punk during the 80’s have come to be remembered as one of the few instances of an uncorrupted musical art form during that decade. Time has allowed the sins of corporate media to come into focus, and Punk has risen as a conceptual antidote. Unfortunately its dominance in our consciousness, due to no fault of its own, does a disservice to the diversity of creative ambition during the period. It was not alone. The historical truth is far more complex and stretches across a diverse spectrum of communities and sound.

My love of Jazz traverses its entire history, but mainstream Jazz during the 80’s is one of the most abhorrent creations that I can call to mind. It makes my skin crawl and my blood boil. If there were three figures from the decade I could eradicate from history, I would choose Regan, Thatcher and Wynton Marsalis. It may sound harsh, but I stand by my words. Marsalis was destructive and regressive. Heralded as a child prodigy, and a vision of African American potential, the man and his music were bound to the rise of neoconservative value systems, and the fall of ideological Black self-determination embraced by the Jazz vanguard, and the communities from which they sprang during the 1960’s and 70’s. Though undeniably brilliant, intellectual and articulate, Marsalis was a PR scheme for the worst of America’s industrialized creative machine. He was a shill. He dangled a carrot which said “if you play by the rules, all this could be yours.” Freedom exchanged for conformity and control. Unfortunately, a great many creative luminaries, facing obscurity and financial struggle, followed him down the dark hole of the decade, and in so doing, did their legacies and discographies a great disservice.

Though his music is awful and should be avoided at all costs, it is not entirely the source of my distaste. It is Marsalis’ proposed model for African American identity, and his active attempt to rewrite history in the process. As a White man, who was only a small child when he came onto the scene, I have no right to speak to the former. Identity, inherited, proposed or chosen, belongs to those who claim it. I am not Black, therefore I cannot speak to its meaning, even when it’s complicit with the nastiest agendas of White America. History on the other hand, is all of our responsibility. Any attempt to corrupt it, or obscure its truths, legacies, or totality, should be attacked and acknowledged as a standing conservative strategy with political agenda. Fortunately these attempts rarely have lasting effect. History has a way of rectifying the biases of its authors and leveling dubious critical evaluations that contribute to it. Its enduring structure has too many authors to be undemocratic, but we should never forget it is always under attack, and it’s integrity the result of a hard fought battle.

Time hasn’t been kind to Marsalis. Most people have come to see him for what he is. I’m sure he will have a place in history, but I doubt his music will be seen to hold value. The immediate danger of what he proposed has passed, but aspects of his revisionist idea of history endure today. The most striking of these is Ken Burns’ critically heralded documentary Jazz. Since its release, the film has remained a heavily cited reference. It should never be confused for a history. It is propaganda for a conservative world view. During its creation, Burns relied heavily on Marsalis as an adviser, allowing the film to be sculpted into a form sympathetic to his Right-Wing agenda. Propaganda is rarely devoid of fact. Its effect is drawn from the strategic use and careful omission of truths. Burns’ sprawling ten part series is an ambitious realization of this. There are truths within it, but its totality amounts to a lie. Though it’s riddled with faults from start to finish, the focus of this piece is its most striking omission – avant-garde and Free-Jazz of the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, particularly those made as part of Afro-Centric, Black Nationalist and self-determinant philosophies. Not only are these some of the most important musical gestures made in the history of music (let alone Jazz), but they are the greatest threat to Marsalis’ legitimacy in history. Were they to hold their rightful place, everything he stood for would be called into question. His attempts to reform history in his own image reveal the evil at his core.

The fact that Burns’ Jazz has rarely been called out for its most striking fault – the gaping hole at its core, should direct us to an awareness of a larger condition. Free-Jazz has almost always labored in the shadows. The fact that few noticed its absence, implies how many people are unaware of its history and importance. My profound love for this music, my belief in it, and my desire to rectify its neglect, was one of the major factors that contributed to my starting this site. The expanded exploration and championing of this music will extend over the life of my writing. My focus here is one its most hard fought realizations – Free-Jazz born in the profoundly conservative context of the 1980’s.

The pressure that artists face from audiences, or the hope for them, is rarely acknowledged in the history of music. We recognize performances that feed off of listeners and grow from them, but we rarely consider the effect of an unsympathetic audience. Few things are more crushing. For an artist to persist under the pressures of neglect is an astounding feat. Free-Jazz of the 1980’s is a perfect example. Not only did the decade strip it of members and reduce its audiences, it attempted to eradicate it from history. That anyone manged to endure and create in the face of such adversity is a profound accomplishment. Even the most devoted fans of avant-garde African American music struggle to cite important contributions to its legacy made during this decade. The propaganda machine did its job well. The shadows drive deep. This is even more tragic because, in my view, some of the most advanced and exciting statements of Free-Jazz were made during this period. It breaks my heart to consider how few people know they are there.

The albums that follow are some of my favorites made during this dark decade. It’s impossible to give a full picture of the remarkable accomplishments achieved during this period of overwhelming adversity. This is not a history, but rather an indication of one. I am neglecting far more than I am able to include. Fortunately, time has been kind to most of these artists. Their names are creeping from the shadows and recognition is beginning to be paid where it’s due. Over the last twenty years I’ve watched the audience and appreciation for Free-Jazz grow. Nothing has made me happier. I doubt it will ever get the attention it deserves, but this seems the sad fate of all avant-garde music. The musicians represented here are survivors and true artists. During the 80’s they managed the impossible and carried on the social and creative revolutionary spirit proposed during the previous two decades – advancing Jazz rather than tainting its history and relinquishing its spirit to conservative control. Perhaps more than anything, they made these albums, brought untold joy into my life, and reminded me that there is always a time to fight.

Muhal Richard Abrams – Mama And Daddy (1980)

Muhal Richard Abrams has remained of the most important figures in Jazz for more than half a century. Calculating his contribution is impossible. He was the seed behind the founding of Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and for 50 years has been its guiding light. Abrams’ effect on music, both through his own efforts, and through those who he inspired, enabled, and taught is immense. This album is his 10th outing as a leader and arguably my favorite. It is a towering piece of work, and like much of the advanced music made by African American artists during the 80’s, defies categorization. Though it is undeniably part of the Jazz cannon, it equally belongs in the company of the entire history of avant-garde composition. With John Carter’s bellow, it offered the inspiration for this piece. I had originally earmarked them for inclusion in Shadow of the Saint, dedicated to the legacy of Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady, but after considering their relationship to the context in which they were made, I decided to set them aside and highlight the credit they deserve. Mama And Daddy features a fairly large ensemble of ten incredible players – Leroy Jenkins, Baikida Carroll, George Lewis, Andrew Cyrille, Vincent Chancey, Thurman Barker, Bob Stewart, Brian Smith, Wallace McMillan, and Muhal, the sum total of which is astounding. Muhal advocates the writing of music (vs full reliance on its spontaneous creation), so though here may be some free-improvising, I would expect that the bulk of the record was composed and orchestrated prior to recording. It possesses an intricate delicacy which rises and falls from the wave of a full orchestra to subtle micro-tonalities and back again. Strange resonances are forced against each other without sustained or sympathetic rhythm. It sounds as though Muhal took the entire history of Jazz, shattered it on the floor and put it back together in an entirely new form. There are remnants of the former, but placed out of time and context to create a new idiom. Its key is in the conclusion. The album closes with its title track, a bizarre, fractured, and threadbare pastiche of Big-Band Jazz and Be-Bop. Here Muhal drops his new construction, and builds a Frankenstein of its former self. The cracks are there. Its form is lopsided. It’s reassembled body, a mirror and metaphor for the whole. This album is simply wonderful. Words will never do it justice.

John Carter – Castles Of Ghana (1986)

When I discovered this record a few years back, it was like getting hit in the face by a brick. John Carter was a sinfully neglected powerhouse. His energy was overwhelming, as a composer he was profound. Unlike many of his contemporaries who fell into obscurity, Carter languished in it for his entire career. His name is not only lost, it was almost never known. Like a number of the artists I’ve profiled in the past, I suspect his obscurity owes to the fact that he from the West Coast. Almost everything Carter put his hand to is worthy of attention, but Castles Of Ghana is beyond belief. It’s a high-water mark in avant-garde Jazz, and easily one of the most exciting records made in any genre during the 80’s. It’s so neglected, I almost never see copies, but when I do they’re in dollar bins. No one seems to know better. Needless to say, I buy it when I see it and give it to friends. I was sad to remove this record from my writing about the legacy of Black Saint. It owes a great deal to Mingus’ finest creation. It’s an off kilter avant-garde Big-Band record of the finest order. Rather than the freestanding atonality often found in Free-Jazz, it utilizes dissonance and tension drawn from tonal and rhythmic friction between multiple players. It’s composition is complex, takes the reins of Ellington and Mingus, and pushes into outer-space. It defies definition, and persists into unknown territory without neglecting its musicological legacy. I can’t begin to recommend this album enough.

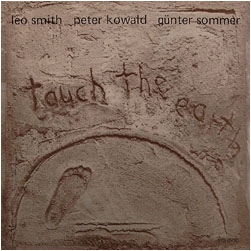

Leo Smith, Peter Kowald, Günter Sommer – Touch The Earth (1980)

Though each member of this trio receives equal billing, I came to it through my love for the music of Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith. Smith is one of America’s most important living composers. With every passing year he pushes sonic exploration and composition to new heights. He’s also a member of the AACM, which should further a sense of the collective’s importance to the advancement of Jazz during its darkest days. In numbers there was strength and resistance. Though this album is a beautiful accomplishment, it isn’t a stone cold favorite. I’ve chosen it strategically. I only own a few albums by Smith from the 80’s, and it was important for me to acknowledge his efforts during this period as part of his continued legacy. Touch of Earth only flirts with the greatness he was later to achieve, but it’s also a different kind of gesture. Where Smith’s more recent albums have been carefully composed, this feels like the result of responsive improvisation. Three musicians listening to each other and reacting. It’s wonderful record which employs the kind of restraint that becomes characteristic of Free-Jazz during this period. Rather than the fire and energy of the 70’s, the careful controlled placement of notes and dissonance comes forward. Both Kowald and Sommer prove to be perfect foils for Smith. The three players dance around each other dropping notes, reacting, and collectively building a beautiful landscape of sound. This isn’t the first record by Smith that I would direct you to, but its a wonderful exploration of sound made at the beginning of one of the darkest eras in Jazz.

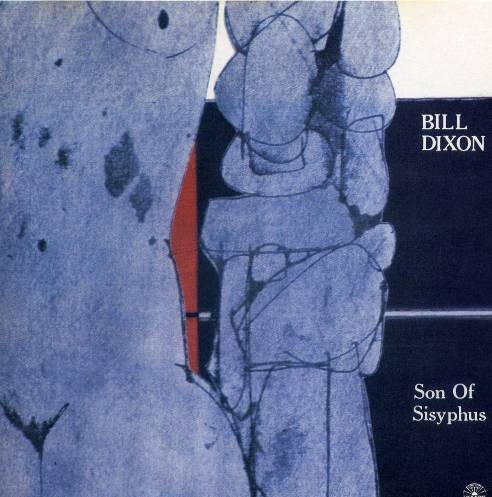

Bill Dixon – Son Of Sisyphus (1990)

Bill Dixon is one of my favorite composers, and Son Of Sisyphus easily ranks in my top ten records of all time. It’s absolutely astounding. It was released in 1990, but recorded in 1988 so I’m bending the rules a little for its benefit. Dixon was a radical figure during the 1960’s – angry, political, and one of his generation’s greatest minds. As a composer he ranks among the best of any era. During the late 60’s his anti-capitalist views and concerns regarding the relationship between race and cultural production, motivated him to remove himself from the music world. He spent the next decade composing and recording in isolation. He didn’t waste a moment. When he returned he was skills as a composer were towering. Dixon only produced a thin discography. Most of his records were released to unresponsive audiences during the 80’s, but everything he touched was gold. His efforts stand as some of the most singular gestures in the history of Jazz, and are even more striking for the context in which they were placed. No matter what I say, I will fail to convey how important he was. Son Of Sisyphus is steeped in restraint and sorrow. It is at once abstract and laced with palpable human emotion. Notes scatter and scrape against each other and disappear across tangible distance. The album is filled with a profound sense of space, unlike anything I can call to mind. It feels as though it has breathed itself into existence with no effort on the part of its composer. It captures a profound depth of emotion and the heights of intellect. If you are unaware of Dixon, I couldn’t thing of a better place to start.

Jerome Cooper Quintet – Outer And Interactions (1988)

Jerome Cooper is one of my favorite drummers. He was an early member of the AACM, and with Leroy Jenkins and Sirone (Norris Jones) was part of the Revolutionary Ensemble – one of the collective’s most exciting collaborations. Cooper made a number of noteworthy solo albums, but to my awareness this is his first attempt as a band leader. It’s a great record which leaves me wishing that he had taken the reigns more. He was an incredible musician and a wonderful composer. I love when drummers write for larger ensembles. Self consciousness fades away and their particular sensibilities show through. Outer and Interactions is a decidedly avant-garde gesture which can’t help being funky. It’s challenging, fun, filled with joy, and defies the easy categorization of Jazz. At moments it flirts the territories of advanced classical music, and at others it sounds like a mad marching band of clowns playing Kazoos. It’s an album I find myself going back to time and time again, never quite able to wipe the smile from my face.

-Bradford Bailey

Very much enjoyed this article. Castles of Ghana — is there another record more deserving of the deluxe reissue treatment?

BTW, you might find these older posts (from a now-defunct blog) to be of interest:

http://destination-out.com/?p=227

http://destination-out.com/?p=228

http://destination-out.com/?p=229

LikeLike

Thanks for this inspiring post!

LikeLike

Very happy you liked it!

LikeLike

Nice to see your withering analysis of Marsalis

he is much richer and well publicized than any of the musicians on your radar

LikeLike